14 Oct

Reposted from NYJA faculty member Jacob Teichroew’s website (read original version here). [Editor’s note: Any opinions and words expressed by the author are not necessarily reflective of any NYJA faculty, staff, or student body.]

MIMESIS AND AFTERLIFE

Posted on October 13, 2014

by Jacob Teichroew

As jazz musicians in a strange period in jazz history, we have to be careful not to want to have our cake and eat it too. These are the most common contradictions I see in the minds of jazz musicians:

• We want jazz to be art music, but not that kind of art music…

• We want jazz be popular music, but not that kind of popular music…

• We want there to be a commercial market for jazz, but not that kind of commercial market…

In our daily struggle to find music in our toils, to find money in our bank accounts, to find lessons in the music that has come before us, we must ask ourselves the following questions:

Are we seeking a voice? Are we trying to find a method of expression? Are we too confined in our approach to studying and playing music?

If we are artisans perfecting a craft, are we willing to accept that our trade may die?

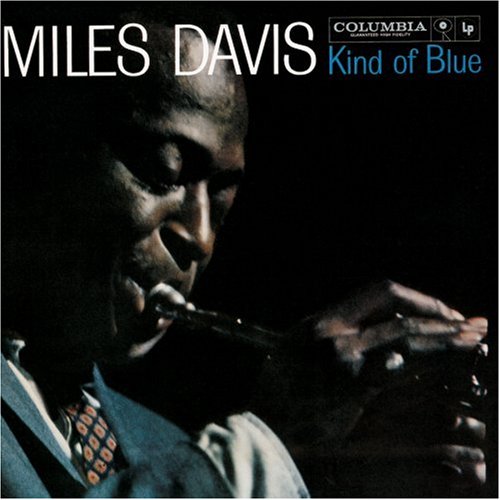

There have been several jazz debate eruptions, and I’ve begun to ignore them because they don’t ever seem to enlighten us. They only serve to make everyone angrier and more confused. But the most recent one, over an upcoming album by Mostly Other People do the Killing that purports to have copied Miles Davis’ 1959 Kind of Blue note-for-note, actually brings up some interesting points.

I should mention that I’m not particularly drawn to the music of Mostly Other People do the Killing, I just find that this particular work of theirs, regardless of its intent, could help answer questions about jazz in a way that resembles a compromise between multiple viewpoints, and could also lead those who play jazz down a fresh path.

The Language in Jazz Discussions

I’m not frustrated with heated debates about jazz as much as much as I am frustrated with the stale, sloppy language that many people use to chime in on these debates, whether they are in Facebook posts, blogs, or Facebook comment sections, or blog comment sections.

Recently, the gnashing of teeth has been over reports that a band called Mostly Other People do the Killing (MOPDTK) is planning to release a note-for-note copy of Miles Davis’ 1959 album, Kind of Blue. One track from the upcoming album, called Blue, has been made available to listen to online. It’s a copy of the track “All Blues,” in which each member of the band plays part of Miles Davis sextet note-for-note.

Regardless of what Mostly Other People do the Killing intended, the recording makes me think the history of art (or at least the history of the word “art”), and it got me thinking about how jazz fits into this history.

Before I start, I know that some people will take issue with the fact that I’m including jazz in the narrative of art. Undoubtedly, someone will say, “But what I like about jazz is that it is not supposed to be academic! It’s not supposed to be pretentious! It isn’t trying to make a philosophical statement, it’s just supposed to be a language!”

On its surface, I think that’s a totally reasonable response, but upon reflection, I notice a few contradictions and inconsistencies. I also take issue with some of the words tossed about by people who hold these views or similar ones.

Artisan – As a way of taking jazz out of the story of art, some may choose to think of themselves not as artists, since that comes with such academic baggage, but instead as “artisans.” I actually tend to think of myself as an artisan when it comes to jazz, because the art for me goes beyond the notes and rhythms. My issue with the word, however, is twofold:

• Artisans exist in the context of a market place. How many blacksmiths do you know? Wheelwrights? Those are two examples of artisans who no longer exist in great quantities because the markets for their trade have dried up. If you think of yourself as an artisan, then you must accept the prospect that your market may dry up, or in other words, that jazz could eventually die…

• If we are ok with thinking of jazz greats like John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, and Wayne Shorter as artisans who have merely elevated their craft to high levels within the expectations of a market place, then is there anything strange about revering them as saints? Have they transcended the expectations of the artisanal trade? If so, then ought we consider them artists? What separates their work from those of mere artisans?

Well, I suppose this is when my other least favorite term will spring up:

Expression – Some argue that Coltrane, Shorter, and other masters have developed such a profound and unique approach, that it’s their self expression that distinguishes them as saint-like figures in jazz.

Well, what is an expression? Most of us will agree that an expression is created when a musician takes a feeling he has, and he expresses it through music.

Many of you are probably thinking “Yeah! Exactly! So what’s the problem?”

Well, art historians tried to use this idea as a way of separating art from non art for many years. But what makes the idea of expression so appealing? Is it that we’ve been drawn intimately close to the initial feeling that the musician experienced? If so, wouldn’t it be an even more glorious thing for him to just have sobbed in front of us, so that we could come into even closer contact with the emotion?

“Well,” you’ll probably say, “it’s not the emotion itself that makes it beautiful and amazing, it’s the fact that he translated it into music on his saxophone.”

That ends up sounding like we’re either just talking about skill on the saxophone, or we’re talking about some other mysterious skill that is hard to pinpoint.

You might be thinking, “Yes! It’s that mysterious skill, we don’t need to name it or get heady about it, it’s just that raw beauty that some people can achieve that makes them masters, and we as artisans are trying to achieve that in our own playing!”

So it’s not the initial emotion that you hold dear, it’s the notes and rhythms that somehow conveyed that emotion in a mysterious way! Fine. So, if it’s the sound of the emotion as played through a saxophone, or created by a sextet for example, then we ought to be able to enjoy the expression even if we are just hearing a recording of it, rather than the live event.

“Yes, duh.”

Ok, then if we hear an mp3 version of the original recording, it should be just as rich with expression, right?

“Yes, for the most part, but the sound quality will be diminished, and it may not have as much of an effect.”

And if we hear another group play the same material note for note, and make a copy of the original recording, it will be just as rich with expression right? Because it’s not the initial emotion, it’s the way the emotion was translated into notes and rhythms on the saxophone, right?

“What?! That’s ridiculous, that kind of copy is just meaningless!”

How, in a medium in which the tradition ask us to transcribe earlier masters, can we draw such an arbitrary line between acceptable copies and unacceptable ones? (By the way, I have to point out that anything I know about jazz I learned through transcription).

This leads me to my third least favorite word:

Voice – Undoubtedly, someone will say, “What!? Transcribing and learning from the masters is not copying! I mean, it starts out as copying, but only with the goal of eventually finding your own voice!”

The idea is that by playing the lines and harmonies (the expressions?) of the masters, someone can find his own method of expression. So, “voice” ends up sounding a lot like “expression.” But as I’ve shown, expression is a weak straw to grasp for, since there is an arbitrary line distinguishing an expression from an acceptable copy of an expression, and from an unacceptable copy of an expression.

On the other hand, sometimes I get the sense that “voice” is just used as a vague, catch-all term to refer to something that’s indescribable in music. But that’s part of the problem: If we don’t really know what we are talking about when we describe good music, then we ought to either find a way to discuss music, or stop discussing it.

We know we can’t rely on “expression,” since it’s not clear when an expression is an acceptable copy of an expression, or when it’s a unacceptable copy of one, and we can’t lean on “voice” since “voice,” if we can even define it without using the word “expression,” is at once vague and narrow, since it doesn’t do a good job of accounting for other important aspects of music, like mood, narrative, and form.

Mimesis

The MOPDTK exchange reminds me of Plato’s forms, and of the ancient Greek approach to art, called mimesis, which held that an art work’s value was contingent upon its resemblance of a natural object. The more closely it displayed a resemblance, the more beauty and truth it contained.

It’s worthwhile to consider that the recording Kind of Blue is itself actually a copy, namely of the live music performed in a music studio in 1959. I suppose that those who scoff at what they perceive as emptiness of the MOPDTK copy hold a mimetic view of art: Since MOPDTK ‘s “All Blues” is a copy of Miles Davis’ “All Blues,” it is removed from beauty and the truth, and is therefore a lesser artifact. By the same token, I would guess that MOPDTK detractors believe that Kind of Blue itself is once removed from beauty and truth, since it is itself a copy of the live music that was performed in a studio in 1959.

Afterlife

It may be the case that the copy of a copy is a lesser artifact, but to me, the value of MOPDTK’s imitative approach lies in the fact that it underscores a possible answer to the big question that his been on everyone’s mind for years: Is jazz dead?

I’m not an artist, or a philosopher, or an art historian, but from what I understand, art historians such as Arthur Danto see the birth of philosophy and art occur at the same moment in history: when artifacts ceased to be purely representational. All successive art, regardless of the artist’s intent, played with the balance between an artifact’s aesthetic beauty and, for lack of a better way to put it, its philosophical statement. The word “art” used to refer only to whatever artifacts most closely resembled the natural world. Then it referred to that which most highly honored religious figures. There was a time when it referred primarily to portraits of rich Dutch people. At some point, after hundreds of years, it became clear that there were no stylistic or philosophical constraints! As Danto observed in the art world obliterated by Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, “there is no special way works of art have to be (from Danto, After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History).” He also saw this as the end of the story of art. Some people probably mistook this to mean that “art is dead,” (sound familiar?) but I think it really just means that we have to change the way we go about making art, and change the boundaries of the set of things that are art works.

The meaning of the word “jazz,” just like the meaning of the word “art,” has gone through a similar evolution. The copy of “All Blues” is meant to remind us that we’ve come full circle, from the development of improvisation, to the creation of swing, to the rogue style of bebop, to post-bop, to ECM, to the unshackling of stylistic constraints. MOPDTK is driving that point home by creating a work that takes its cue from the era of imitation. Just as post-modernism signaled the “final moment in the master narrative” to Danto, the fact that there is no special way jazz has to be signals to us that the story of jazz is over.

But that’s not to say that “jazz is dead.” It just means that we have to change the mental constraints with which we listen to, create, and discuss jazz. Just how, I’m not sure. I do believe that we have to look at jazz as an art, and not an artisanal trade. That doesn’t mean artisans ought to stop doing their jobs well. It just means that we have to accept that jazz as a trade might wither away and die, as trades tend to do.

Alternatively, we can see jazz in terms of an art, each instance of which takes a position in an ongoing debate in an afterlife unfettered by biases and expectations.